Arguments about the definition of Vaporwave show the scene is “active and alive” – Thom Hosken explores the limitations of genres and the role of the gatekeeper.

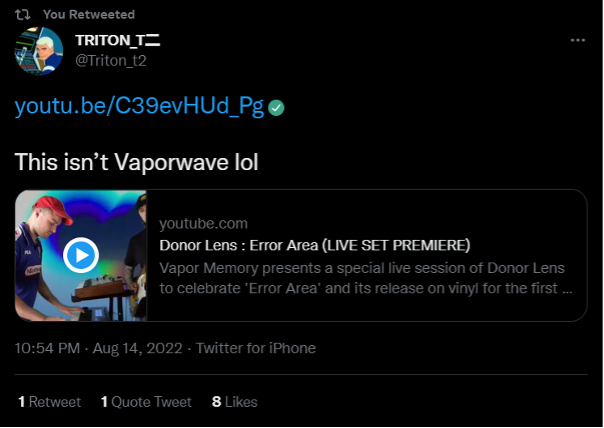

Late this Summer, there was an explosion in social media Discourse™ that coincided with the ElectroniCON 3/Groove Continental events, the production of the Nobody Here documentary film, the release of the Death’s Dynamic Shroud album Darklife, and a Twitter user discovering a Donor Lens session where we committed the cardinal sin of playing instruments and singing.

Beneath many layers of irony and nihilism, the serious point seems to be that Vaporwave has evolved in such a way that the term no longer makes sense, and that it now resembles the kind of commercial product it initially sought to satirise.

I get it. Over the years, I’ve flip-flopped between writing music and writing about music. If Vaporwave in its purest form is a music/art movement that uses samples to express millennial ennui and satirise corporate culture, the music that sticks most closely to this definition is perhaps the most academically interesting and the most fun to write about. People playing instruments and singing happens in every other genre, so it follows that incorporating this makes Vaporwave less interesting or something else entirely.

Amongst the early, unadulterated stuff from the 2010s, there are true gems and truly radical art with Eccojams and Floral Shoppe lasting long in the imagination and inspiring legions of imitators. But, a cautionary tale: as a dorky kid, I used to trawl Allmusic.com for 5-star albums, seeking the purest representations of niche genres and collecting these classics on CD. These would usually be early albums from totemic figures, before they or their musical movement ‘lost their way’. I was a walking, talking ‘I prefer the early stuff’ guy. Cringe.

Is it not actually more academically interesting and fun to observe and participate in an active scene, even if there’s an element of the Soap Opera or MMORPG to the way the story unfurls? To go to gigs and listen to records as they are released, rather than wait for history to sort the texts into a canon? To make music the way we want to and call it Vaporwave if we think that it is a useful descriptor, and even if it’s little more than a useful marketing tool (© George Clanton). We can’t go back to 2010, nor should we. Most of the music from that time still exists (though some has slipped poetically into the ether), and very few of those OG artists sound like they did a decade ago. The decision to make ‘classic vaporwave’ is one option amongst many, and is itself now a nostalgic act. Many of the Old Guard (Christtt, Skeleton Lipstick and Luxury Elite notably) are passionate supporters of newer artists.

It is hyperbolic to suggest anyone has truly entered the commercial world, with the exception of one Superbowl halftime show director. And no one is making more than pocket money from streaming royalties – it is or was a myth that artists have cleaned up their act re: copyright in order to secure Spotify playlist placement. Naughty uncleared music exists in abundance there, though some acts like DDS have recently removed their most egregious examples as a precaution. It must be said that a lot of this critical noise is drummed up by people with their own projects and products to shill – we’re all equally tainted by commerce.

Vaporwave has some unique qualities, but it doesn’t exist in isolation. It has forefathers and close cousins in music concrète, tape music, dub, plunderphonics, chopped & screwed and hauntology – all of which used recorded sound as its raw material. Vapor is distinct mainly because it uses the internet to create and propagate itself, and it is simultaneously nostalgic and current. There are many ways to do it: Vaporwave does not have a fixed form. This is a feature not a bug and its built-in capacity for adaptation/regeneration is probably what has kept it from actually dying, despite constant proclamations to the contrary.

Its practitioners are nearly always expatriates from other scenes – indie scenesters, metalheads, punks, jazz nerds, classical composers – seeking a more suitable community that shares their Catholic tastes. With all these kids in the sandpit, it is inevitable that boundaries (no matter how broad) are going to be challenged, especially the apparent edict that you’re not supposed to play instruments or sing even if the resulting music is good. They’ve seen all this before – Steve Reich’s early tape works being critically preferred to his later pieces that combined tape and classical instruments/emulated tape techniques in notation; interminable debates about what is/isn’t ‘punk’; the astonishing vitriol directed at Miles Davis by Stanley Crouch for daring to change with the times and push jazz forward.

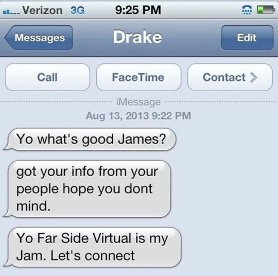

There has been erasure of things that were present from vaporwave’s inception – the compositional, MIDI-heavy Utopian Virtual of James Ferraro’s Far Side Virtual, and even the ironically-titled Genre-Specific Xperience by Fatima Al Qadiri that has become detached from our lore, even though dozens of 2020s vapor records sound just like it. Vaporwave isn’t and never was about simply following the Floral Shoppe formula. Great artists like FM Skyline, Eyeliner, and eventual infinity belong in this lineage.

Even ‘sample-free’ artists in our scene such as Runners Club 95 engage with sampling and internet culture by using one-shots, loops, presets, and referencing fashion & memes in their titles & artwork in a way that makes them legitimately vaporwave unlike, say, Glass Animals slapping generic a e s t h e t i c visuals onto their bland indie pop music. There really aren’t many opportunistic interlopers or bogeyman masqueraders in our scene – even those at the most ‘indie pop’ wing either served a legit vapor apprenticeship (George Clanton/ESPRIT 空想) or have been doing the same thing from the start (Whitewoods).

It is inevitable that there will be disagreements within the community, but that in itself is likely a sign the scene is active and alive. Maybe the shit-stirrers are a necessary part of the ecosystem too – playing the heel in this kayfabe. The early records had magic and ideological purity for sure, and they still (mostly) exist for us to enjoy. The old-timers have memories of the period and young uns can imagine what it was like. Our bubble is not without its faults, and I have long felt it could do with being more critical and less happy-clappy at times. Ironically, critics like Anthony Fantano and Pitchfork have recently started engaging with us, and specifically the kind of ‘problematic’ vaporwave-adjacent music that initiated this debate in the first place.

My main issue with the rise of post-lockdown IRL vaporwave is that the shows tend to take place in the largest cities in the richest countries, excluding those in further-flung places who previously needed only an internet connection to participate. But that is part of a broader diversity debate that ties in with anonymity (how often does an intriguingly masked artist, sometimes one with a female name, turn out to be Just Some Bloke from a trendy town?). Maybe the real radical act in 2022 is to show your face and sing songs? Even if not, it’s undoubtedly a valid option. And if we think the geography of Vaporwave is becoming predictable, it’s up to us in other parts of the world to put on our own shows and create our own local scenes.

In my guise as Wichita LimeWire, I recently made an album Upload 2 Me that puts mainstream 2010s culture under the microscope. Looking back, the artefacts of that era seemed ugly, ancient and strange. We should be driving our subculture forward, not looking to return to these times even if that was a possibility. You can’t put the genie back in the bottle, and telling artists what they should/shouldn’t be doing (or that they need ‘saving’) is the surest way to get them to do the exact opposite.

Written by Thom Hosken

One response to “The Story of ‘That’s Not Vaporwave’”

[…] It’s a fair point, and besides, I’ve yet to see anyone argue that Vaporwave NEEDS to move on from its roots in sampling. It’s a topic covered in detail by Thom from Donor Lens on this platform. […]